Historically, we are now at a safe distance from viewing Complaints or even The Shepheardes Calender as belonging to Spenser’s Minor Poems – relegated to a kind of eternal secondariness. The editorial practice of distinguished twentieth-century editions from Oxford to the Variorum has long been superseded by more student-friendly texts edited by Bill Oram and others for Yale, and Richard McCabe for Penguin, where the non-Faerie Queene verse is more neutrally presented as The Shorter Poems. 1 Not secondary, not less important, just less long. Nevertheless, even the “Shorter” designation has problems in amalgamating publications such as the miscellaneous Complaints (1591) alongside the love poetry of Amoretti and Epithalamion (1595); both the Yale and Penguin editions are invaluable for scholars yet rather indigestible for students in the sheer diversity they present in tomes of around eight hundred pages. The edition of Complaints we are editing for The Manchester Spenser aims to reinscribe a sense of the singularity of that book with its varied yet analogous contents, and the very different profile it gives for “the new Poet” with its mixture of laments, beast fables, translated sonnet sequences, and dangerous satires of court. 2 Part of this work has underlined to us the powerful consensus of previous editors in favor of the 1591 Quarto (Q) at the expense of the 1611 Folio (F) edition. This article looks again at the evidence of the 1611 text in the service of exploring the material conditions of Spenser beyond The Faerie Queene in the period just after his death, when his reputation was consolidated.

It is only natural to assume that an edition printed during an author’s lifetime (and whose printing the author might even have overseen himself) is by default the definitive text, and that we must be skeptical of any changes in later versions. 3 But it would be wrong to assume that because Q was printed during Spenser’s lifetime its text is faultless and does not contain any elements that Ponsonby or Spenser would have wanted to change or correct if given the chance. To judge the quality of F’s text fairly, we consequently need to evaluate it by the three criteria that constitute a good (early modern) reprint:

1. Accuracy (i.e., identification and correction of errors vs. introduction of new errors).

2. Reader-friendliness (i.e., presenting the text in a way that allows contemporary—and potentially also modern—readers to access it more easily than the first edition).

3. Sensitivity to the text (i.e., evidence of an editor or proof-reader who is aware of the text’s meaning and of its poetic properties).

In this context, it is useful to consider the corrections of Q itself as a point of comparison. That surviving copies of Q contain various combinations of corrected and uncorrected gatherings suggests that proofreading happened during printing. During that proofreading process, some mistakes were caught, most of them typographical errors, such as “dearh” for “death” in The Ruines of Time (RT) 52 (probably caused by an r in the compartment for similar-looking t's in the print shop), “Melpomine” for “Melpomene” in The Teares of the Muses (TM) (probably caused by a compositor with limited knowledge of the classics using phonetic spelling), or “Vimnial” for “Viminal” (probably caused by misreading a manuscript written in secretary hand) and “hardie head” for “hardiehead” in The Ruines of Rome (RR) sonnets 4 and 11. 4 In the case of these and all other Q corrections referenced in this article, it is possible to tell from the presence or absence of unambiguous errors in the respective gathering which is the corrected version: “Melpomine” appears in the version of gathering E that also has TM 47 beginning “Gan griefe then enter…” (the other version reads “Can,” which editors as well as F unanimously agree is the correct reading), while “hardie head” appears in gathering R, the same as “Vimnial,” which is evidently the result of a compositor misinterpreting the seven minims of “Viminal.” 5

Other changes strike us as more significant—and possibly even authorial—in nature. These include the insertion of the participle “neighing” in Mother Hubberds Tale (MHT) 654 to complete the line, 6 the changing of the phrase “did slily frame” at the end of Muiopotmos (Muio) 370 to “framde craftilie” so it fits the rhyme scheme, or the spelling change from “scatter” to “scater” in the final line of RR sonnet 30, resulting in an improved visual rhyme with “gather.” 7 Still other corrections made during the printing of Q strike us as more trivial because they involve changes that might be put down to the individual preferences of a particular compositor. These are mostly changes to punctuation, such as the addition of a comma after “Linus” in RT 333 (arguably not a vital change, although the comma has a rhetorical function, so the line is improved by its presence) or the change of “down” to “downe” in VB sonnet 9 (both of which were standard spellings and used interchangeably in 1591). 8 Other changes were not caught by the proofreader of Q, however, and persisted even into the corrected versions. These include the clearly accidental spelling “beee” at the end of TM 566 (quietly regularized to “bee” in all modern editions), “Mansolus” in RT 414 and RR sonnet 2, “Speheards” (for “Shepheards”) in Virgils Gnat (VG) 233, or the irregular italicizing of “Abysse,” “Faunes,” and “Satyres” in TM 260 and 268. The latter are preserved by modern editions, although those words are not being used as proper nouns in TM, so this is what an early modern compositor would have considered a formatting error. 9

Evaluating F’s accuracy essentially amounts to considering two questions: how well F is able to identify and correct errors in Q, and how many of F’s changes to Q’s text introduce actual errors as opposed to merely minor differences that we might consider unnecessary. Regarding the former question, F identifies and corrects a number of demonstrable errors. For example, it removes the clearly erroneous triple vowel in TM 566, turns the “Speheards” into “Shepheards” again, corrects “Mansolus” to “MAVSOLVS”, and sets “Abysse,” “Faunes,” and “Satyres” in roman type. It also corrects Q’s “couertize” to “couetize” and “words” to “worlds” in RT 363 and 574, and amends Q’s “louing tongue” in TM 600 to a more intuitive (and likely correct) “liuing tongue,” and “stalkes” in RR sonnet 30 to “stackes” (also likely to be correct given its context). Other corrections have been viewed more skeptically. For example, F’s correction of “singulfs” in TM 232 to “singults” is often regarded as an unnecessary regularization—although it is a logical correction, considering that Spenser appears to have been the only author to use this variant of “singult” (which suggests he used the form erroneously). 10 Despite those exceptions, however, the fact that modern editions typically adopt the majority of F’s corrections is a testimony to the edition’s accuracy. By contrast, F appears to introduce no changes that demonstrably create textual errors, although the presence of some Q errors, such as “displacing” (for “dispacing”) and “Enfested” (for “Enfestred”) in Muio 250 and 354 suggest it was set from a copy of Q that contained some uncorrected gatherings.

The relative reader-friendliness of F compared to Q is best assessed by considering the intuitiveness of the punctuation of F. Q’s punctuation is relatively sparse and, as a result, some lines in Complaints are not immediately self-explanatory and may require readers to reread them and consider their context to understand them fully. Examples include RT 676–7, a couplet that in Q’s original punctuation reads: “Giue leaue to him that lou’de thee to lament / His losse, by lacke of thee to heauen hent,”. In context the speaker is addressing the “Immortall spirit of Philisides,” so the meaning of the lines can be roughly paraphrased as “permit one who loved you to lament the fact he has lost you, now that you have been taken to heaven”—but that meaning is far from obvious at a first reading because of the enjambment and the less-than-straightforward syntax. Without additional punctuation, readers may initially interpret “lament” as an intransitive verb and consequently misread the first line of the couplet as “permit one who loved to mourn for you [to do something that will be specified in the next line],” which in turn creates further problems when parsing the second line, because failure to spot the enjambment will make “His losse” appear to be the subject of the next clause (i.e., that which is being “hent” to heaven). 11 The person who prepared F for print evidently recognized the problem, because F adds punctuation that, while perhaps not fully grammatical, enables readers to read out the lines in a manner that will make their meaning clearer: “Giue leaue to him that lou’d thee, to lament / His losse by lacke of thee, to heauen hent,”. Placing a comma after each “thee” encourages readers to pause briefly, which allows them to chunk together the correct combination of words in the first line (i.e., “him that lou’d thee,” not “thee to lament”) and to recognize the implied relative clause in the second line (i.e., “thee [that art] to heauen hent”). As a result, F’s punctuation of these lines is clearly superior to Q’s in resolving an ambiguity that can hardly be regarded as intentional and enabling even modern readers to understand the lines more easily.

While this level of ambiguity is admittedly rare, there are numerous instances in which the combination of Q’s minimalist approach to punctuation and Spenser’s approach to syntax can cause readers to stumble during a first reading. Additionally, some of the punctuation in Q is counterintuitive and likely erroneous. Modern editions typically respond by lightly adjusting and modernizing the punctuation in order to facilitate understanding. In a number of cases, this effectively restores the punctuation of F, such as in RT 497. In Q, this line ends with a comma, whereas F corrects this to a full stop. In context, RT 497 concludes not just a stanza but the first stanza of the first “tragicke Pageant,” which like all of the other pageants is divided into two parts. 12 The first stanza establishes the splendor that subsequently falls into decay in the second stanza, so F’s full stop is far more intuitive than Q’s comma; indeed, this is the only stanza in the whole Q text to end with a comma rather than a full stop. This suggests Q’s comma is likely to have been accidental. Punctuation marks are small, so compositors could easily confuse commas and full stops or semicolons and colons. With the exception of Renwick’s 1928 edition (whose text is effectively a facsimile of Q), all modern editors opt for a full stop. 13

F’s approach is generally closer to the principles of rhetorical punctuation, in which commas, semicolons, and colons do not merely follow grammatical necessity but indicate where, and for how long, the reader should pause. As a result, F’s punctuation occasionally seems excessive compared to modern conventions, but it is in fact significantly more helpful than Q’s punctuation for reading Spenser’s poetry aloud, which is how most of his contemporaries are likely to have read it. F not only allows readers to distinguish between minor and major caesuras (an aspect that is particularly central in TM, a poem that revolves around the concept of subtle, nuanced variation on a familiar theme) but also to follow the meaning of syntactically complex lines of verse. However, there are moments where even such a perceptive reader as the person responsible for F’s punctuation changes meets his limits. In Q’s version, RT 214, which describes Leicester being slandered after his death, reads: “And euill men now dead, his deeds vpbraid:”. The reference of the phrase “now dead” may not be fully clear to a reader at a first glance, so the line could easily be misread as “and evil men, who are now dead, blame him for his deeds,” rather than “and, now that he is dead, evil men blame him for his deeds,” which is the intended meaning. F attempts to tackle the ambiguity by adding a set of brackets, turning the line into “And euill men (now dead) his deedes vpbraid:”. Grammatically, F’s brackets only serve to make matters worse in seeming to identify the evil men as the ones who are now dead—which is of course nonsensical, because they can hardly be blaming Leicester from beyond the grave. In rhetorical terms, however, F’s brackets are a (modest) improvement over Q’s comma, because they flag up “now dead” as a parenthesis and allow readers reading out the line to pause at the right moments, and hopefully to recognize in the process that “now dead” in fact refers back all the way to the first line of the stanza (211), which is identical in Q and F and runs, “He now is dead, and all is with him dead,”. 14

F’s reader-friendly rhetorical punctuation is not always strictly necessary in grammatical terms, but it is worth noting that it is only rarely inferior to that of Q in terms of clarity. Another noticeable feature is that such punctuation is mostly clustered during RT, TM and, to a lesser extent, VG. The poems in the second half of F, which lacks MHT, feature significantly fewer punctuation changes. 15 This uneven spread of punctuation changes may be an indication that they were not spontaneous decisions of a compositor but corrections contained in a marked-up copy of Q that F was set from—perhaps even a copy marked up by Spenser that had come to Lownes via Ponsonby’s papers, as has been posited by Andrew Zurcher in relation to the 1609 Faerie Queene. 16 But even if that copy of Q was marked up by someone other than Spenser, that someone was not only a stickler for rhetorical punctuation but also—unlike the majority of the early readers who copied the poems from Q into their miscellanies and sometimes made nonsensical changes to lines—a perceptive reader with a sound understanding of Spenser’s poetry. 17 Historically, F has been criticized for its attempts to “regularize” Q by adjusting some of its more eccentric spellings (given that early modern spelling is fluid but far less arbitrary than modern readers are inclined to think, this criticism is probably unreasonable) and to improve the flow of the verse by trying to avoid metrical irregularities (which is a more controversial matter). 18 What has been overlooked in the “regularization” debate, however, is the fact that at least in the case of Complaints, F is highly sensitive to the poetic properties as well as the content of Spenser’s verse, which is particularly apparent in cases where changes affect the meter of a line.

Q contains a number of lines that require metaplastic manipulation in order to become iambic. In some cases, readers are merely required to distinguish between a monosyllabic and a disyllabic version of the same word, some of which Q indicates through differences in spelling, such as “worlds” / “worldes” or “wings” / “winges” (and it is another indication of F’s perceptiveness that it notices and preserves this distinction). 19 In other cases, such as “And efte in Dolons slye surprysall” in VG 536, even metaplasm will only go so far, because the line requires readers to stretch “surprysall” to four syllables (i.e., something like “surprys-y-all”), a solution made even less convincing by the fact that this happens to be the earliest known instance of “surprisal.” In F, the phrase reads “subtile surprisall,” arguably not an elegant solution, but unlike in Q’s version, all that is required to make the line metrical is a (subtile) shift of stress. At the same time, it preserves the content of the line (“subtile” can be used as a synonym for “sly”; see meaning 1a in OED), 20 as well as its alliteration, while preserving—and perhaps even enhancing—the interaction of sound patterns between the adjective and the noun in the original: “subtile,” whose “i” is evidently meant to be sounded here, not only shares the vowel sounds of “surprisall” but also its final consonant, which almost turns it into an internal rhyme. In short, it is the sort of clever change that Spenser himself may have chosen to make had he wanted to rework the line (and considering the original line is hardly one of his best, it is not inconceivable that he might have wanted to). A similarly perceptive metrical adjustment happens in Muio 149, although this time it is perhaps not so much intended to resolve a metrical irregularity as an ambiguity of meaning. In Q, lines 147–50 read:

While the proximity of “champion” to “fields” and “country” may indicate a pun on Clarion being a valorous fighter (cf. the description of his arming in Muio 56–104), the words refer to landscape features, so they also point towards “champion” in the sense of “champian” or “champaign,” i.e., a plain or expanse of open country, which is the primary sense here. 21 F, seeing the need for clarification, adjusts the spelling and, apparently in an attempt to avoid the trisyllabic pronunciation that is a metrical possibility but not typically used by Spenser, adds a syllable to the line. 22 Thus the line in F reads, “And all the champaine o’re he soared light,”. While we may regard the added syllable as unnecessary and the simultaneous use of disyllabic and monosyllabic “over” in the same stanza as slightly inelegant, the symmetry created by F’s amended line is not dissimilar to circular structures that can be found in FQ – indeed, when the epic uses “champian” it is always disyllabic—so again, this is a type of adjustment that is in tune with Spenser’s verse, if not actually by him.

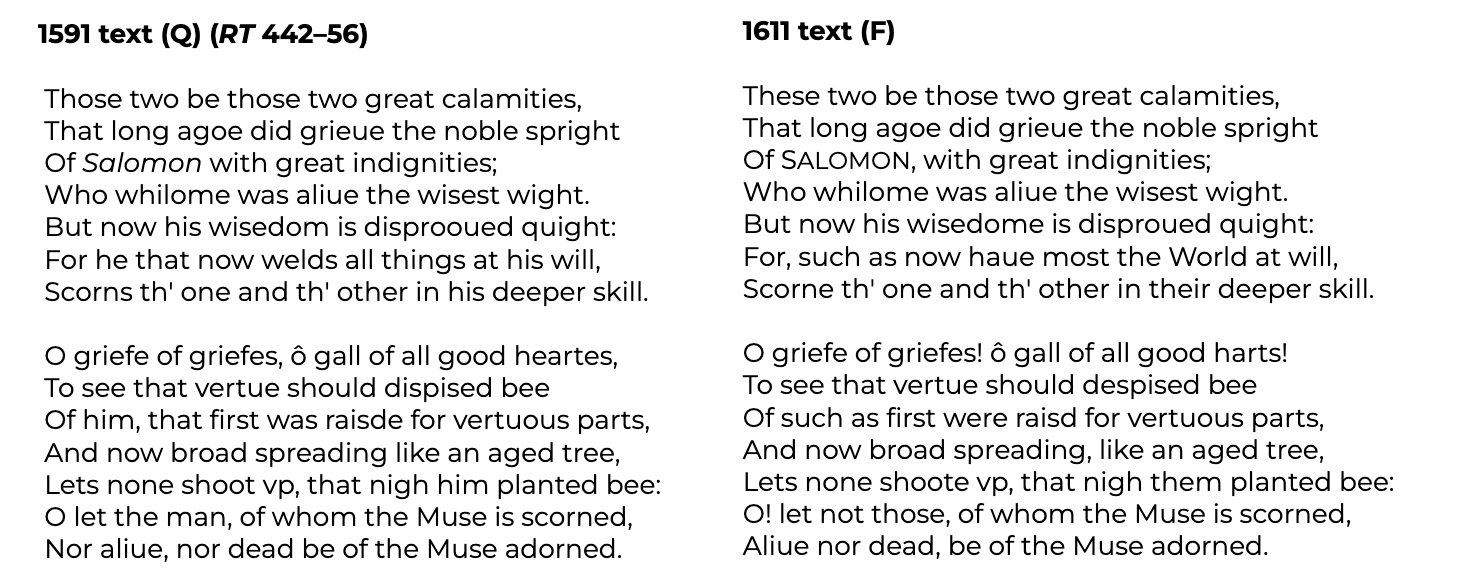

The quality of F raises the question whether editors of Complaints should perhaps not be quite so quick to dismiss the best-known textual difference between F and Q: the anti-Burghley passages of RT, the poem whose text F revises most carefully and most perceptively. While those revisions have traditionally been read as the result of posthumous censorship done on the part of Lownes to avoid offending Burghley’s son, Robert Cecil, the earl of Salisbury, at least two of those lines—the concluding couplet of the second anti-Burghley stanza (454–5)–could be regarded as metrically superior in F. 23 In Q, those lines read: “O let the man, of whom the Muse is scorned, / Nor aliue, nor dead be of the Muse adorned.” While it is grammatical, the second line of the couplet requires readers to elide its beginning to “Nor ‘liue, nor dead.” This is caused by the fact that the first line does not contain a negation, which means that the first “nor” in the second line is grammatically necessary and cannot simply be dropped for metrical reasons to enable the beginning of the line to read “aliue nor dead.” If F’s only concern were to remove the reference to “the man” believed to be Burghley, the easiest way to censor the line would have been to simply replace it with “such men” or “those men,” that is, to repeat the generalizing strategy F uses to emend ll.447–48. What F does, however, is to bring the “not” that is only implied in Q’s version through the double “nor” forward to the place where it most naturally belongs: after the main verb. As a result of this choice, F is then able to have the second line begin at “Aliue,” so that the resulting couplet reads: “O! let not those, of whom the Muse is scorned, / Aliue nor dead, be of the Muse adorned.” In addition to the rewording of the first line and the dropped “nor” in the second, F adjusts the punctuation of the couplet. The exclamation mark after “O” for a brief dramatic pause may have been due to the preference of a particular compositor (for which there is considerable evidence throughout F), 24 but the decision to move the comma is interesting because it means the comma shifts from highlighting the word “aliue” in Q to highlighting the word “dead” in F, which is arguably more in keeping with the content of the line, while also signaling more effectively to readers which words should be linked together.

To be sure, other considerations are necessary when editing a text as controversial as RT, so our text will include both Q and F passages to enable the reader to make a judgment as to which is preferred. We present those passages here so that readers of Spenser Review can also have that sense:

In context, the censored passage follows the praise of the recently deceased Walsingham as Meliboe, which adds a layer of complexity to the F rewriting. Where Q coordinates the praise of Walsingham as a patron of learning and (slightly surprisingly) of soldiers, with the miserliness of an unnamed, Burghley-like individual, F’s attack is a more generalized assault on “such as now haue most the World at will.” The same difficulty is visible in the second stanza where the pluralized skinflints sit rather uneasily with the image of such patrons as “an aged tree.” 25 As we have suggested, however, the rewriting is neither crude nor unintelligent: iambic meters are made more regular, while the sense of exclusion from patronal systems is even more starkly articulated in the first stanza, and perhaps more directly anticipates the outburst of absent-patron-woe in the next poem in the collection, TM. We are no longer just talking about the faulty “will” of one mean Cecil, but a “World at will” of those uninterested in learning or indeed “men of armes” (RT 441). The critical force of the F text has arguably not fully been canvassed by modern Spenserians, even though ironically this is the version of the text Ben Jonson read with considerable attention. 26

Jonson is a good place to end this essay. In his copy of the 1617 Folio, in effect a straight reprint of 1611, 27 Jonson scribbled on the page containing the censored passage (H2) that “Salomon was grieved w<ith> this consideration,” a concern which Riddell and Stewart suggest underpins the Cary/Morison ode. 28 Jonson crouched over his copy of the Lownes Folio offers a powerful corrective to the editorial tradition which has slightly downplayed the authority of that text, and more broadly, to the idea that Spenser was predominantly the poet of The Faerie Queene. Complaints likely was devoured by younger poets keen to see the practice of satire in MHT and indeed RT (a point perhaps emphasized by the many manuscript copies of the poems which postdate Q). 29 This suggests yet again that the profile of Spenser as a stylistic and political conservative has been exaggerated to the detriment of how he was actually read during the early modern period. Our forthcoming edition of Complaints will situate the poems more thoroughly than has been the case up to this point both in Spenser’s reading and in how Spenser himself was read and imitated by his followers. “He became his admirers,” W. H. Auden wrote shortly after the death of W. B. Yeats in 1939, “he is scattered among a hundred cities / And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Charting how Complaints was reread in the decades after the 1590s gives a renewed sense of Auden’s frosty yet generative truism, “The words of a dead man / Are modified in the guts of the living.” 30